On our trip to Siem Reap, we went to the landmine museum founded by Aki Ra. The landmine museum in Cambodia was established by Aki Ra to inform people of how much of a problem landmines are and what effect they have on people in Cambodia. This museum has Aki Ra’s work and story, what kind of landmines were dropped in Cambodia, how landmines affect people today and how they are moving forward from the past. Aki Ra created the landmine museum in hope that one day landmines will be wiped from existence.

Aki Ra’s parents were killed by the Khmer Rouge when he was at a young age. He was then orphaned and placed in a Khmer Rouge camp later becoming a child soldier. With the Khmer Rouge he acquired his first gun at the age of ten years old. He would go out and plant landmines for the Khmer Rouge. When the Vietnamese army invaded Cambodia to destroy the Khmer Rouge he was captured by Vietnamese soldiers. Later Aki Ra would join the Cambodian army and his duties would be to plant landmines on the border between Thailand and Cambodia. After the war using the knowledge he gained about landmines while he was a soldier, Aki Ra would return to the villages that he placed mines during the war and he would remove all the mines by hand. Aki Ra would take the disarmed landmines back to his house as a collection. Tourists soon heard of a Cambodian man who was disarming mines and unexploded ordnance and took an interest. Aki Ra charged tourists one dollar to come see his collection. Eventually, the government of Cambodia told Aki Ra that he had to close his collection due do to safety issues and stop disarming landmines by hand because they did not deem it safe and up to standards. Aki Ra complied with the wishes of the government and stopped disarming landmines, getting a license for disarming landmines just a year later.

Cambodia is one of the most heavily mined places in the world because of over thirty years of conflict. Demining organizations estimate that there are at least four to six million mines and unexploded ordnance in Cambodia. There are two different types of mines in Cambodia, Anti-personnel mines which are meant to blow your arm or foot off and anti-vehicle mines meant to stop vehicles. Not including the unexploded bombshells that were dropped by the United States. These were dropped by the U.S. forces during the Vietnam war and sometimes the bombs don’t work and are left unexploded for years. Landmines can lay dormant yet active in the ground for decades until something or someone sets it off.

People in Cambodia today are affected greatly by landmines. Today many victims are missing limbs and have burn marks on their bodies as a result of landmines. Landmine victims have common troubles including being unable to provide for themselves and having to beg on the streets to make ends meet. Others have to rely on their offspring and other members of their family to help them get food and shelter. There are also groups of landmine victims that have become musicians and play traditional music at temples to support themselves and their families.

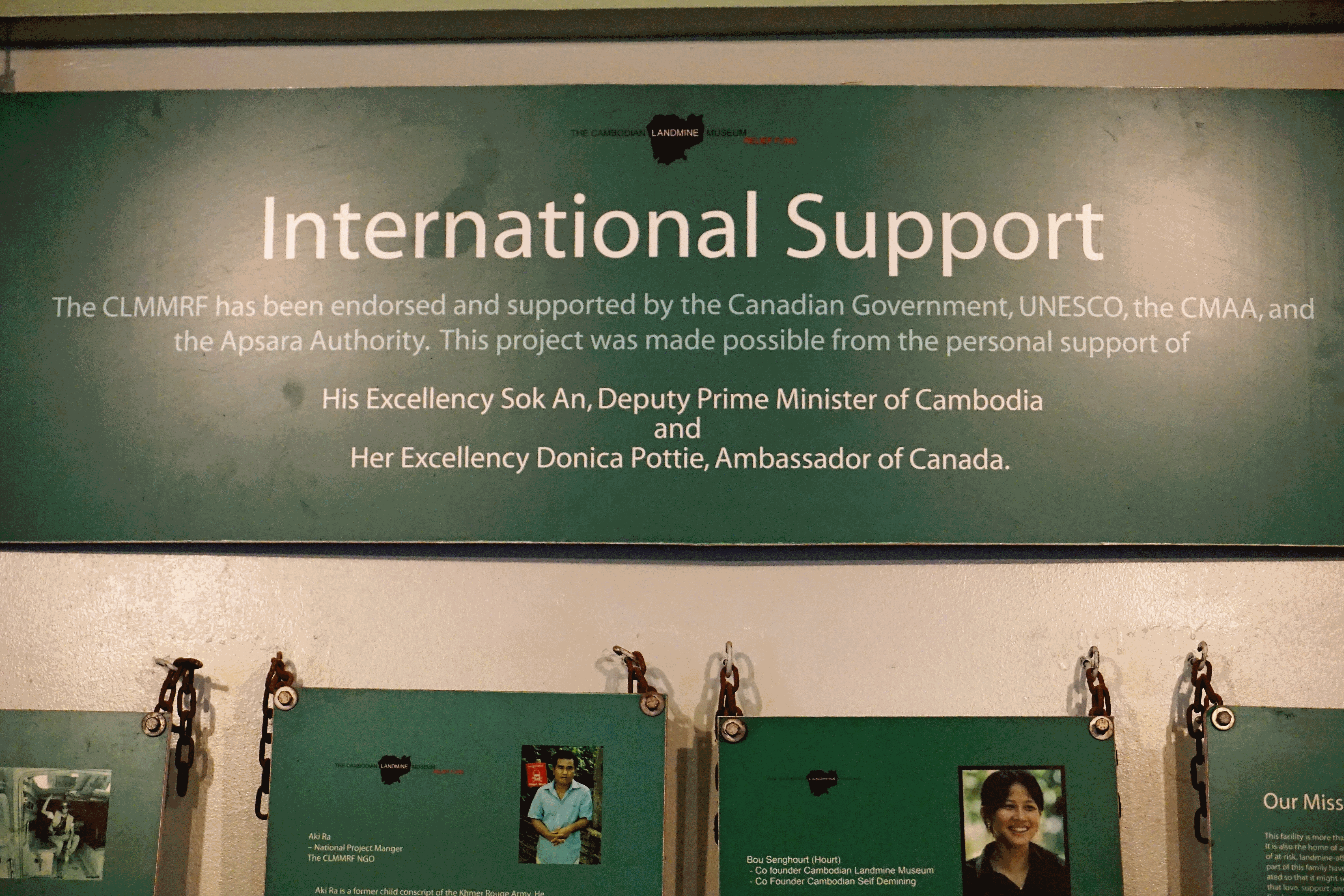

The world is coming to agreements to protect civilians from the continued use of landmines by forming organizations like the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL). In addition, demining organizations are sprouting up to help remove landmines in countries like Cambodia. Some of these organizations are native to Cambodia like the one Aki Ra founded The Cambodia Self-Help Demining (CSHD). The world is slowly removing landmines by forming campaigns and Non Government Organizations (NGOs) but it will still take many years to remove the existing mines from Cambodia and stop the continued use of landmines.

Landmines are a serious issue but with organizations like the CSHD removing landmines they are cleaning up a mess the world has created. As a citizen, you cannot go out and remove landmines because it is not safe, but you can donate to NGOs removing landmines from previous conflicts. You can also support the total elimination of landmines by pushing governments to extend treaties and holding your government accountable to honor the treaties signed to ban landmines. In the future, we hope that landmines are eliminated from use because the after effect is devastating to civilian populations. The rate of landmine deaths go down every year but we hope that one year the number will be zero. –Anton Chell 07/02/2018

Sites Used

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aki_Ra

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambodian_Landmine_Museum

http://www.cambodialandminemuseum.org