A not so random thought.

Reading Colley (2012) my first reaction was, I need to share this article! I need to talk this one through with those I work with. I even had the article ready to share with a manager, also in a PhD program, as an ‘interesting case in a period of change and austerity not unlike our own times’ but I stopped myself, unsure at how such an article would be received, even in an environment encouraging ‘brave conversations’. The intention was not to suggest this is my/our current reality but, given the nature of work in the public sector, ethical challenges do occur and our failure to acknowledge, problematize and learn to work with/through have real costs and consequences. I wonder if I hesitated because it would go against the organizational performativity I feel obliged to engage in?

I work in an institute that is actively engaged in pursuing cultural change and which has made a commitment to developing policy and practices related to Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Anti Racism and Decolonization (EDI +). Our Culture Day included keynotes by Dr. Dwayne Donald who, with the metaphor of the fort, highlighted coloniality in curriculum and Junetta Jamerson who challenged us to actively engage in anti racist practices. In break out sessions we were encouraged to dismantle, create, learn and teach for social justice. This requires both learning and unlearning. However, “learning requires a context of at least some security, of trust in the environment and other persons who populate it” (Colley, 2012 p.318). If I am hesitant to share a journal article with another student, I wonder if enough work has been done to build trust in the workplace and/or if the current economic /social conditions for the desired learning around EDI+ to occur exists?

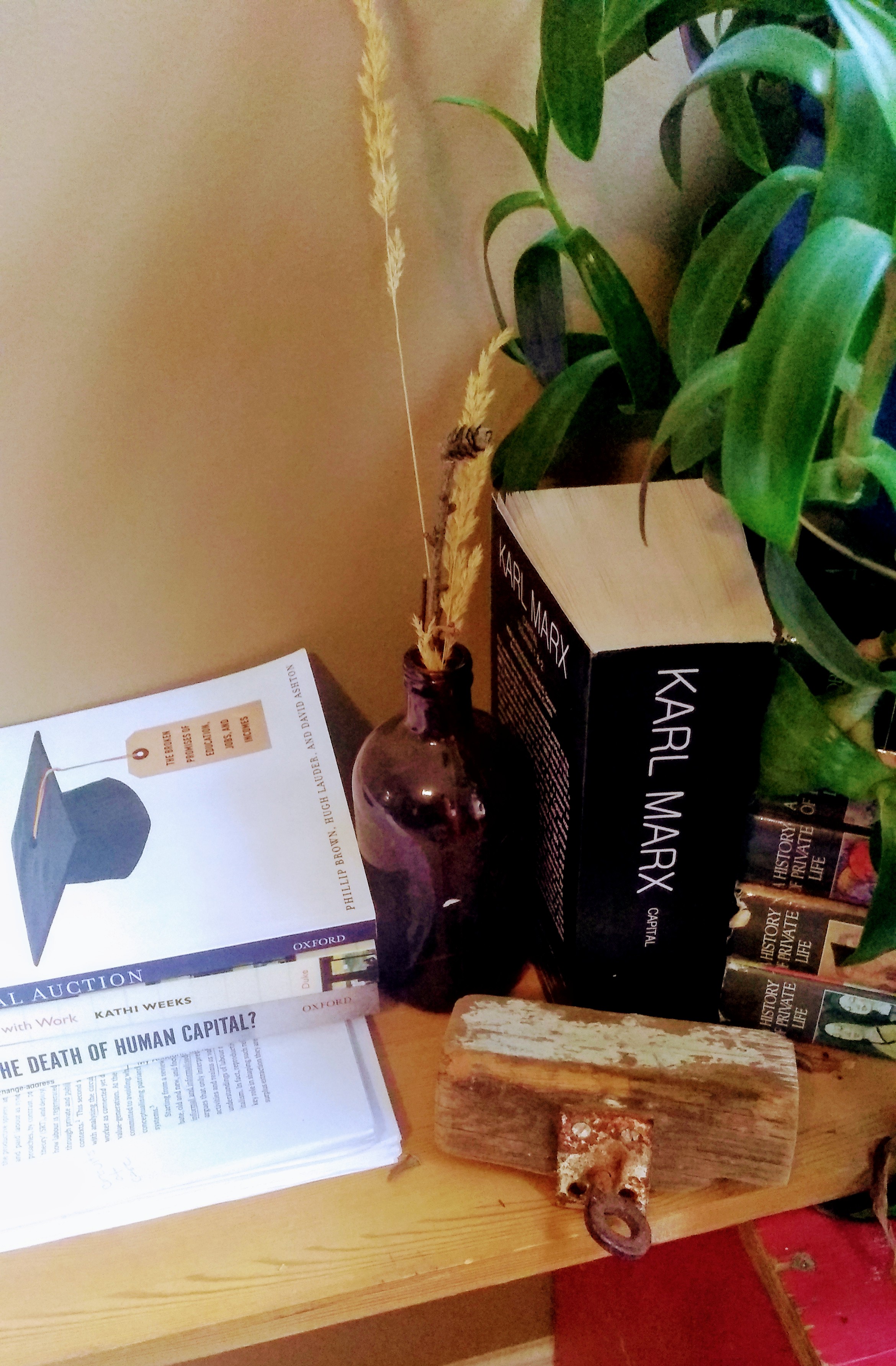

Canada is sold to (in)voluntary (im)migrants as a society of opportunity, but as Brown, Lauder & Ashton (2011) argue the trap of opportunity is

“… making people increasingly self-centered, stressed and unfulfilled as more and more effort, money and time is spent doing what is necessary than for any intrinsic purpose”( p.141).

When I consider education and training for newcomers to Canada in relation to Shan’s (2009) scholarship exploring credential and certification regime (CCR), I am struck by and deeply uncomfortable with the incongruencies between stated EDI and the processes, practices, programs and policies within post-secondary institutions that support “…a system of selection and exclusion, producing structural segregation” (Shan, 2009 p.359). Declarations are made for decolonizing learning within post-secondary institutions yet the same institutions offer programs specifically catering to populations who experience a devaluing of training and credentials that are deemed too ‘foreign’, too outside some Western standard or whose education and learning has followed a non-Western trajectory. Where is the consideration for other worldviews or ways of knowing and being ? Institutions might argue they are responding to industry demand for ‘standards’ and ‘accountability’ but they also profit from narrow and arbitrarily set standards. I am left wondering who or what EDI intended to support? Is it a tool or space for social justice or a form of ‘woke-washing’ intended to maintain market share in the education industry?

What do I do with this awareness, this ethical discomfort with these practices and the role I (in)directly play in the process? Colley argues the tension of navigating ethical practices is a form of work. I wonder if this work is inherent to paid labour, as there is always the potential for conflicting values as well as an inequality in power or is it, as suggested, a product of or exasperated by a managerial state and audit society?

In regards to the discomfort, Colley suggests I “..must decide whether to pursue conscientious objection, compliance, or adopt a stance of ‘principled infidelity’” (p 322). Having a voice and a stage to object, feeling the necessity to comply, or the compulsion to commit an act of infidelity is always shifting and situational, tied to position, location and perceptions of power and access, costs and benefits. Where are my stages (especially in a time of COVID) and who do I speak to/for? How many times do I speak before I learn to be silent, to comply? When is infidelity – cheating, straying, being unfaithful the most honest act?

Another thought

In a recent webinar I mentioned that I listen to podcasts during walks (In Defense of Domestic Workers), but thinking about it afterwards, I realized this is no longer the case. Over the past year, I have come to consume podcasts as I work not as I walk. Teaching online has shifted the nature of my labour. Rather than spending 4 hours a day in direct contact with learners, I am spending those hours (plus many others) developing high quality content that learners can engage in asynchronously and independently. This can, at times, become a technical process, requiring too much concentration to mentally complete other tasks but freeing enough to absorb new thoughts and ideas, as I cut and paste lines of html code and reformat materials for predictability and accessibility. I do not identify with this technical labour in the same way as I did when working directly with foundational learners, and I am not sure how I see this work. The potential for surveillance and demand for standardization bristles against my self-image as a professional, skilled practitioner. My ability to respond to emergent learner needs, and to capture ‘teachable moments’ seems reduced in an environment that requires the ‘front loading’ of work.

I recognize that I have developed new skills, not only technical but also relational. I welcome the little voices and tears that ‘interrupt’ our lessons, reminding me of the important work that is happening. I am honoured to be welcomed into my students home and humbled by the grace they offer as we muddle through learning together. Is my identity as a teacher and mentor challenged sitting alone with my podcasts? Probably. Do I feel alienated from my work? Somedays. Would I feel more connected if I went into ‘the building’ each day. I am not sure.

I can identify some of the learning that I have experienced over the past year, working and teaching in this new reality. What is more challenging and/or uncomfortable to identify is the non learning that I might be engaged in during this period of austerity, change and uncertainty.

What have I learned or not learned about my work that I would hesitate to share a journal article?

“There’s room at the top they are telling you still…”

Reference

Brown, P., Lauder, H., & Ashton, D. (2012). The global auction: The broken promise of jobs, education, and incomes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Colley, H. (2012). ‘Not learning in the workplace: Austerity and the shattering of illusio in public service,’ Journal of Workplace Learning, 24, 5, 317-337.

Shan, H. (2009). ‘Shaping the re-training and re-education experiences of immigrant women: The credential and certificate regime in Canada,’ International Journal of Lifelong Education, 28, 3, 353-369.