I heard that you built an invisible fence

What about us? What about your friends?

It’s difficult not to take offense

When you’re running into an invisible fence

Relational practice, our ability to “work with others”, be friendly and supportive, polite and thoughtful in order to foster and improve workplace relations in the service of organizational goals, is both highly coveted and illusive within the workplace. Holmes and Marra (2004), extending Fletcher’s analysis (1999), suggest that relational practices fall under four themes: preserving (the mundane and tedious but necessary work), mutual empowerment (project advancing but other-orientated) , self achieving (aimed at improving the effectiveness of the individual) and creating team (the background conditions for the group to flourish). Holmes and Marra (2004) contend that relational practices most often become ‘evident’ through: indirect comments; humour; off the record ‘hallway conversations’. While often gendered as female practice, Holmes and Marra (2004) found that community norms had a greater impact on relational practices than gender.

One thought I had in relation to the article was the im/balance that occurs under the four themes of relational practices. Who is ‘allowed’ to carry out what type of relational practices? Who is ‘taking on’ the preserving practices and who has the privilege of engaging in self achieving practices? A middle aged male, racialized as white, may be given space to use humour to diffuse an uncomfortable situation, while a queer, Gen Z’r might be perceived as rude or unprofessional using the same tactic. One’s position may impact relational practices while in turn, relational practices may shape one’s unofficial ‘status’ within the workplace.

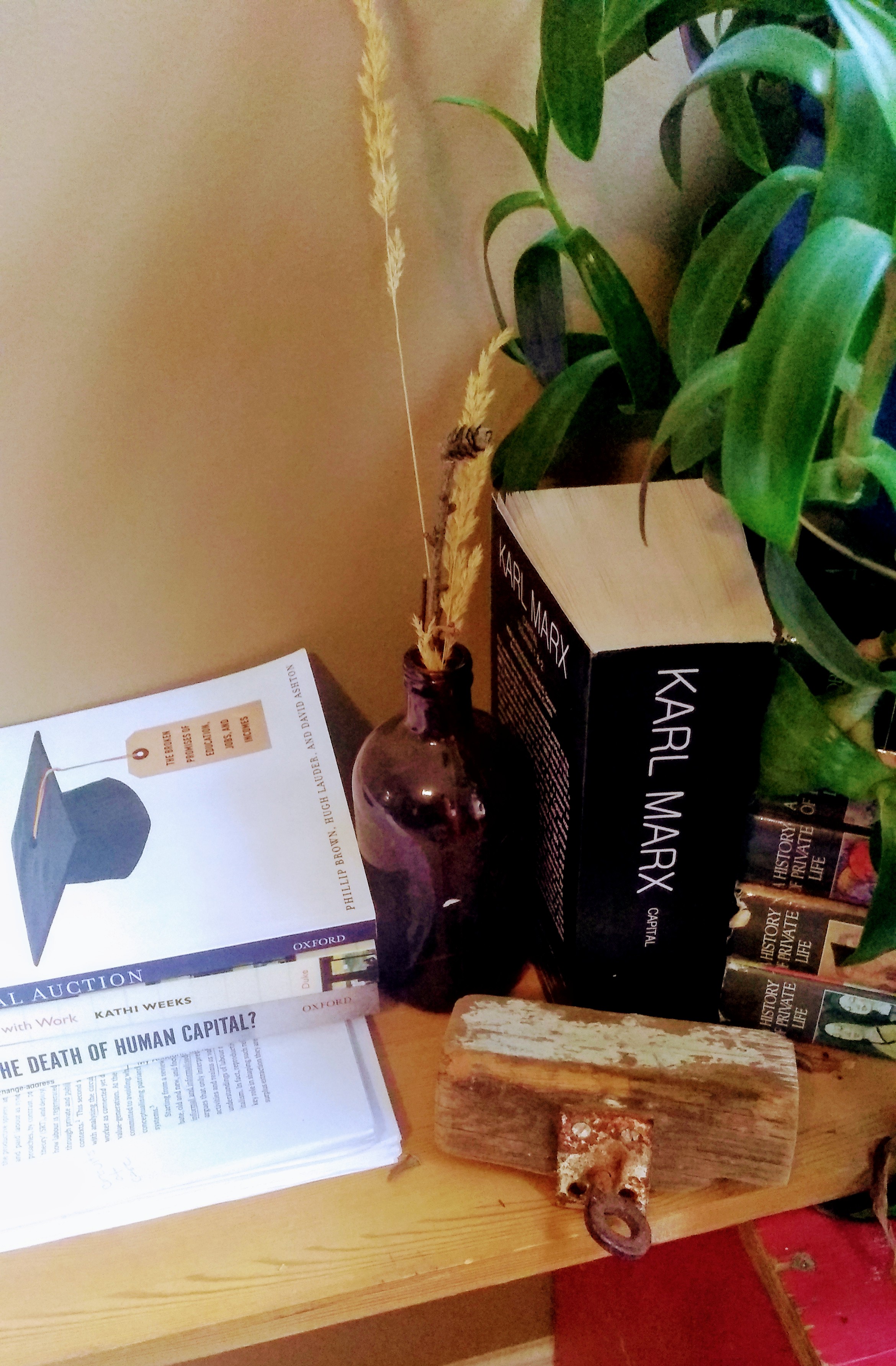

A second thought has to do with the invisibility of relational practices. In the competitive labour market, highlighted in “The global auction: The broken promise of jobs, education, and incomes”, one is always seeking to ‘level up’ skills, qualifications and accolades. In many workplaces, this is documented and surveilled through performance management processes and/or software . If my supervisor relies on ‘ invisible’ relational practices to offer recognition for good work, it’s not ‘recorded’ and I can’t use the feedback as ‘evidence’ of my success. Likewise, the ‘damage control’ extended to a less ‘competent’ colleague is not recorded. Does this really matter? I think it might. In the field of education, operating budgets are being slashed, and programs are being downsized. Whose job is secure? Who is let go for not being quite as ‘good’? There is the ‘official’ documentation that is used to sort and cull employees but there is also a tacit, ‘unofficial’ scorecard that comes into play that is not accountable or transparent. What is ‘remembered’ and what is ‘forgotten’ may (dis)advantage some (communities of) workers. And as this is all ‘invisible’ there is little room for advocacy or recourse.

This (in)direct leads me to Sara Ahmed’s (2012) article, “On being included: racism and diversity in institutional life”, in which she writes about the challenges and contradictions of work intended to institutionalize diversity. A sentence that stood out for me is, “When the rules are relaxed we encounter the rules” ( p39). I wonder if relational practices represent, at times, a relaxing of the rules and in those moments we are made acutely aware of approval or castigation? Does it become apparent who can ‘go to the pub’ and who stays in the office to complete the preserving tasks? One can see how relational practice competency may be connected to the institutional cloning or ‘good likeness’ that Ahmed observed. Those who can bring comfort in reflection, Ahmed argues, are recruited, retained and promoted. If it is whiteness that inhabits a space, then it is whiteness that is reproduced. The invisibility of relational practices may (un)intentionally reproduce whiteness regardless of the institutional goals.

I find the reference to institutional goals in Holmes and Marra (2004) interesting in light of the commitment of so many institutions and organizations to addressing issues of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI). These can be important goals, however, as Ahmed points out:

“… the recognition of institutional racism can easily be transformed into a form of institutional therapy culture where the institution becomes the sick person who can be helped by receiving the appropriate therapy” (p.47)

What are the therapies on offer? Pop a few vitamins of intercultural training? A course of anti-bacterial anti-racism workshopping? A bit of blood letting to purge ourselves of a few bad racist? Paint a mural and celebrate our diversity? A wellness approach of meditative reflection and mindful practice? The last offers the soft pillow of suffocation as opposed to a brick wall to bang against.

Is the patient cured, “When the diversity is so ‘evident’ that it can be assumed that the box has been ticked”? As I scroll through Facebook, a Maclean’s article “How to prioritize diversity, equity and inclusion in the workplace” sponsored by Canadian Business, pops up telling leaders EDI is more than just filling quotes. It includes, they suggest “Going above and beyond traditional hiring by looking globally and providing immigration support, language-skills training and team-integration assistance” and “[e]nsuring that clients are able to be served in their language of choice” in order to be a “…high-performance businesses that energize our economy, even in the toughest of times” (March, 2021). EDI for some has become an opportunity to import skilled labour who can be “trained” and “integrated”, or perhaps cloned, within the boundaries and structural constraints of the organization (Fuller, et al 2005) for the goal of expanding client bases. Has EDI become co-opted, monetized and depoliticized? Was EDI ever committed to diversity/social justice work? And can diversity/social justice work occur within institutions and organizations?

Diversity practitioners, Ahmed argues, strive for “…diversity to go through the whole system” (p.28 italics original) implying that the ‘cure’ is found beyond the efforts of self-improvement, beyond policy, curriculum and the course offerings of the institution. It goes up the ladder to include those who fund institutions, to government agencies, philanthropic organizations, and the public/private funders of research and development. Nothing less than systemic change. That is a tall order.

This week the new Alberta K-6 “Curriculum” was released, which according to Minister of Education, Adriana LaGrange is, “ ensuring that our students have that rich, essential knowledge and skills…” (Corbella, March 2021). Such essential knowledge includes the “the concept of money” (Gr.K) and learning about “business and trade” in (Gr.2), that “[m]ost Albertans are Christians” and “…newcomers bring new and unfamiliar religions, faith and practices..” (Gr. 6), that “[s]ome Black Albertans overcame prejudice and achieved individual success” , “Chinese and Indian immigrants suffered racial discrimination”(Gr.4), and “Alberta aspires to be open, welcoming…” but immigrants “must pass a test” (Gr.6). I could go on. By age 12, the children of Alberta will learn “…the nation offers hospitality and even love to would be citizens as long as they return this hospitality by integrating, or by identifying with the nation (Ahmed, 2012 p43). A white, Eurocentric, Christian nation focused on money, business and the individual with little tolerance or consideration for ‘others’.

That a document like this could be presented and supported as a curriculum, is evidence of embedded, structural racism and a deeply ingrained faith in free market capitalisms, entwined in a symbiotic relationship. I used to think the questions were, where to start and how to do justice work right? Not so much anymore. There are millions ‘started’ and doing justice work but their voices get lost in the cacophony of life and the moments of stagnation can leave diversity/justice workers feeling like they are banging there head against the wall. In my own small efforts, I move between feeling agentic and skillful (Vincent & Braun, 2013) to futile and invisible. On my more cynical days, I am challenged to see beyond the performativity of EDI therapies and I am beguiled at the resources (money, time, talent) spent on stage props. When I am presented with public work like the K-6 curriculum I can be overwhelmed at the scale and level of work required. And when I read the comments in social media or the words of ‘experts’ in the press I wonder, does anyone even care about fairness or justice? And this is multiplied in a hundred ways through the course of a week.

Thankfully, as I sit and drink my coffee this morning, I am hit by a wave of thoughtful critique and humour, side comments and tiny actable snips of advice from small communities engaged in local actions: letter writing and documentation, fact checking and zoom ‘teach ins’, for doing the mundane work towards mutual empowerment. I am thankful for the relational practices of these folks. Dr. Evelyn Hamdon’s metaphor of social justice work as gut bacteria, tiny invisible acts capable of breaking down matter and creating fissures, making the invisible visible over time, came at an opportune moment, as did the words of Angela Davis picked up at from a neighbours free sidewalk library and finding the first dandelion of the season. Perhaps the question is not how to do social justice work, but rather, how to maintain hope that social justice work can be done and how to nourish and grow the efforts?

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham: Duke University Press. Chapter one: Institutional Life, pgs. 19-50.

Brown, P., Lauder, H., & Ashton, D. (2012). The global auction: The broken promise of jobs, education, and incomes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fuller, A., Hodkinson, H., Hodkinson, P., & Unwin, L. (2005). ‘Learning as peripheral participation in Communities of Practice: A reassessment of key concepts in workplace learning,’ British Educational Research Journal, 31, 1, 49-68.

Holmes, J. & Marra, M. (2004). ‘Relational practice in the workplace: Women’s talk or gendered discourse,’ Language in Society, 33, 377-398.

Vincent, C., & Braun, A. (2013). ‘Being ‘fun’ at work: Emotional labour, class, gender, and childcare,’ British Educational Research Journal, 39(4), 751-768.